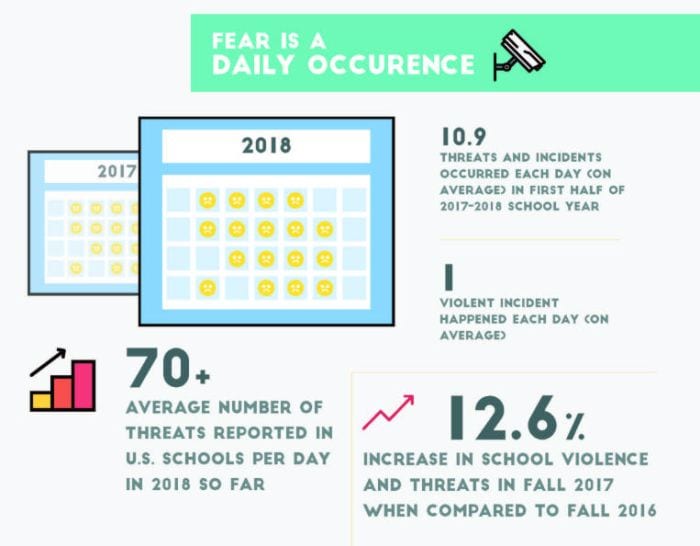

It’s no secret that violence seems to be on the rise in schools, especially at the elementary level. Teachers report more aggressive behavior than ever before, aimed at both other students and teachers themselves. This uptick in student violence has teachers on edge, worried for their own safety as well as their students’. Many feel helpless in the face of it and question their choice of career.

Perhaps it’s best summed up by a Facebook post by teacher Annie Demczak that reads:

… I love all my students. I love the students with trauma. I love the students with mental illness. I love the difficult students. I love the violent students … because I’m a teacher and my heart is made of glitter and marshmallows and happiness and rainbows. Loving little people with abandon is what I freaking do.

But sometimes, loving someone looks like setting boundaries. Consequences. Hard conversations. Seeking additional support. Reporting dangerous behavior. Standing your ground. Finding alternative placements.

Stop worrying if you’re tenured.

Stop saying “they’re just kids.”

Stop being scared of the parents or of administration.

Stop wondering if you should tell someone.

Stop giving up because no one will do anything.

Stop thinking you should be PHYSICALLY assaulted and VERBALLY berated at your job.

Stop thinking that having intense anxiety and depression surrounding your workplace is NORMAL.

It is not okay. This is not what we signed up to do.

You are a wonderful, caring, amazing person who has the biggest heart for wanting to help little people … but don’t you dare think that it is OKAY to be ABUSED and TAKEN ADVANTAGE OF at your workplace. We would never tolerate it in any other area of our lives. This is no different.

But what, exactly, should teachers do? The We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook sees regular postings from teachers asking for help dealing with student violence. We’ve put together some of the best responses to give teachers assistance in dealing with this difficult topic.

1. Protect yourself and your students in the moment.

Scary as it is to contemplate, think now about what you’d do if a situation turned violent. Have a plan in place to protect your students and yourself. Teacher Suzanne advises, “Stay calm. Have your class ready to leave in a minute if the room is unsafe. Whom do you have that you can call for help? Can you get someone to sit in the room with the child if your class has to exit? Can you get the child escorted to the office? I was always able to grab another teacher on prep to help in emergencies.”

Talk to teachers in nearby classrooms and discuss what you’ll do if student violence arises. Your administration should already have plans in place regarding the procedures for dealing with these situations. Make sure you know what they are. Have the numbers for anyone you should call already programmed into your phone to save time.

Don’t try to break up a physical fight between students unless you’ve had training. You could wind up getting hurt and then be unable to help other students and fellow teachers. Teacher Scott recommends looking into classes from the Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI). “I went over 15 years ago, and when I had to recently break up a fight between two 11-year-olds, it kicked in like a reflex. It’s good training to keep you safe around violent kids.” Ask your administration to enroll you or set up a program for your school.

2. Equip yourself with practices that reduce these occurrences.

Violent outbursts rarely happen out of the blue, and establishing self-regulation practices and a school culture of belonging can help rewire students’ brains for regulation and resilience instead of anger and violence.

According to Dr. Becky Bailey, creator of Conscious Discipline, rageful acts often happen because of a hypersensitivity and hyperreactivity in our fight-or-flight system. Students who are prone to outbursts require consistent, relationship-based interventions that soothe their overly vigilant systems. “You cannot punish the aggression out of a child. The only pathway to peace is through healthy relationships and targeted interventions focused on connection, healing, and the teaching of self-regulatory skills,” Dr. Bailey said.

In the classroom, focus on connection points like greeting each student when they enter the classroom. Notice the cues that might indicate a child is having trouble and seek help before the situation escalates from upset to outburst. Designated calming spaces like a Safe Place self-regulation center can provide tools, strategies, and practices to use every day in the classroom, and intermittently in more targeted sessions with school counselors. Transitioning your In-School Suspension to a Calming and Recovery Environment (C.A.R.E.) room like Ridgeview Elementary in Liberty, Missouri, can also help reduce behavior issues and violent acts.

3. Document, document, document.

Once the event is over, find time as soon as possible to record everything that happened in writing. “Write everything in your professional notebook,” says Carla, a teacher on the We Are Teachers Helpline. “Include all the details. If you don’t have time at the moment, try to use a voice recorder from your cell phone for your notes. Be specific on the date, place, time, and situation in your notes. [Then] remember to write it down on your laptop and save it. Anything can happen to a notebook. That’s your evidence. Try to find a witness that can support your evidence.”

If you have a student who is frequently violent, documenting may be helpful to them as well as you. Tania explains, “Write everything down, dates [and] times, and see if there is a pattern to why he is acting [violently]. Is it a certain time of day? Ask him: ‘Why are you so angry? Are you hungry? Is someone bullying you?’ Let him know if he needs to talk to come and see you. Have a calming spot where he knows if he is feeling angry, he can go there to calm down then come and talk. Is there another student/family member in the school he can talk to during those times to help him calm down?”

Whether student violence is a onetime occurrence or all too frequent, documenting it all in writing every single time is an absolute must.

4. Inform your admin, school counselor, or social worker.

Make sure all support staff, as well as parents, are in the loop about violent incidents. Some teachers feel they should keep quiet because it shows they aren’t managing their classroom effectively. Never let those kinds of fears keep you from speaking up.

Teacher Christina advises, “Please document and communicate with your admin and behavior specialist/guidance/school social worker (whoever is available on your campus). They should help you to come up with a plan to start with tier 1 interventions, as well as help you follow the process to determine if this student needs to move to tier 2 or 3 for behavior interventions.”

Students with diagnosed conditions like oppositional defiant disorder may qualify for accommodations like a classroom aide or intervention specialist. As you formulate plans, consider looking into alternate behavior-management strategies like restorative justice.

Above all, as a teacher, remember that you have a right to expect your administration to be supportive of you in these situations. If they dismiss your worries despite documentation or leave you to handle it on your own after you’ve asked for help, this should raise serious red flags about your school.

5. Inform your union.

Speaking of rights, in many places, teachers are unionized and have specific rights regarding harassment or dangerous situations. Teacher Colleen emphasizes, “You have rights. Are you a member of a professional organization or union? If not, find one in your state and pay those dues. Call them. Tell them what happened. In my state, Georgia, they provide a lawyer to advocate and protect you. We are not a union state, but I’m a member of a professional organization.”

Renee agrees. “Never be too nervous to talk to your union. That is exactly what they are there for and why you pay your dues. They know legally what can and should happen to protect you, your students, and your district.”

Your union’s legal advisers can also help you decide when and if you need to contact law enforcement. Some states or schools require student violence to be reported to the local police. That can feel overwhelming, so don’t try to navigate it on your own. Use all the help that’s available to you.

6. Know when it’s time to leave.

Only you can decide how much student violence is too much for you to handle. For some teachers, one major incident, especially without good administrative support, is all it takes. Others develop strategies for dealing with it over the years, though they often find it wears them down over time. Be honest with yourself and remember that it’s not weak to step away from ongoing violence, especially when there doesn’t seem to be an end in sight.

Listen to teacher Lee: “Trust me, as a teacher of 18 years who did stay in such toxic situations—leave. Nothing is worth the effect this will have on you mentally and physically if you stay. … You deserve to be treated with dignity and respect like any other employee in any other organization.”

7. Take care of your mental health.

Whether you stay in your job or leave, find someone to talk to about how student violence has affected you. Chat with a counselor or therapist. Visit a support group for victims of violence. Find a group of fellow teachers who know what you’ve been through. You’re not alone in facing student violence, even if you feel that way right now. Help is out there—all you have to do is ask.

Additional Resources

Administrative and colleague support is vital for teachers. Learn how to recognize a toxic school culture before you take a job.

Conscious Discipline helps teachers integrate social-emotional learning, discipline, and self-regulation into their classrooms so they spend less time policing behavior and more time teaching vital life skills.

For free webinars, podcasts, articles, and more, visit Conscious Discipline’s Free Resources page today!